Epinephrine has been a mainstay in cardiac arrest treatment since the early days of resuscitation. When I first learned advanced cardiac life support, epinephrine was administered to “every pulseless individual,” or so the mnemonic went to help remind the importance of this first line pharmacologic agent. On the positive side, epinephrine increases ATP production by releasing stored glucose, which in theory provides energy for the myocardium to contract during the low flow state of cardiac arrest. Epinephrine also constricts the arterioles and increases coronary artery filling pressures, increasing blood flow to the myocardium. Epinephrine is not without downsides, however. The arterioles supplying the brain are also constricted, decreasing blood flow to the brain. This may worsen post resuscitation ischemia secondary to decreased blood flow. Epinephrine also activates platelets promoting thrombosis. Epinephrine also increases myocardial force of contraction, increasing oxygen and energy expenditure, potentially worsening myocardial ischemia. Epinephrine has been studied in several trials, including comparing regular dose to high dose epinephrine. A large observational study looking at epinephrine in cardiac arrest had inconclusive results.

The PARAMEDIC2 trial, an almost 3-year randomized trial designed to answer the question “does epinephrine make a difference in cardiac arrest?” was undertaken as a collaborative among five different National Health Service ambulance services in the UK. In the trial, patients were randomized to receive doses of either 1 mg epinephrine or normal saline administered every 3-5 minutes for cardiac arrest that did not respond to CPR and defibrillation (if indicated) in line with current guidelines. This was a very well-done study for several reasons. One, it was prospective, or looking forward where the treatment vs no treatment was decided before the trial began and followed forward as opposed to a retrospective study, which looks back through charts of patients who were treated in the past. The PARAMEDIC2 trial was randomized, where medication kits containing either epinephrine or normal saline were assigned randomly to the patients and no-one, not the paramedics or hospital staff knew what the patient received. This blinding is an important to remove bias among providers caring for the patient so further care and decision making were not based on whether the patient received epinephrine or saline. Finally, there were just over 8000 patients enrolled in the trial. This sample size was large enough to minimize the possibility that the outcome occurred purely by chance. Primary outcome of the study was 30-day survival between groups. Secondary outcomes included survival to hospital admission, survival to hospital discharge, favorable neurologic outcome at discharge, survival at 3 months and favorable neurologic outcome at 3 months. To measure favorable neurologic outcome, the modified Rankin scale was used to evaluate the neurologic outcome.

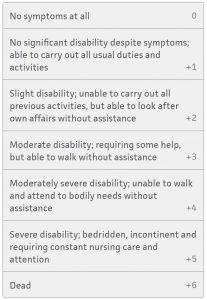

Modified Rankin Score

The primary outcome, or survival rate at 30 days, was 3.2% in the epinephrine group and 2.4% in the placebo group. A significantly higher rate of patients survived to hospital admission in the epinephrine group, 23.8% vs 8%, however survival to hospital discharge was much closer, while favoring the epinephrine group with 3.2% vs 2.3%. Survival at 3 months also favored the epinephrine group at 3% vs 2.2%. when it comes to comparing favorable neurologic outcomes at discharge and at 3 months, however, no difference was found between the two groups, meaning the rate of favorable neurologic survival was about the same, 2.2% vs 1.9% at discharge and 2.1% vs 1.6% at 30 days. In drilling down further looking at just neurologic function at hospital discharge, significantly higher number of patients had modified Rankin scores of 4 or 5 in the epinephrine group compared with the placebo group. The authors concluded that while using epinephrine compared with placebo improved 30-day survival, there was no significant difference in rates of favorable neurologic outcome between the two groups.

What are the implications for the medic in the street? This study raises questions not about the efficacy of epinephrine improving survival but asks a larger, more profound question regarding satisfactory neurologic outcome. The study group presented information about the study to nearly 300 lay people participating in first aid instruction and 95% of the participants responded that they valued long term favorable neurologic outcome over short term survival. In speaking with many patients and families, this appears to be a viewpoint held by the vast majority of people. So where does this leave us? While there does seem to be a survival benefit to epinephrine, it is clear that this is at the cost of favorable neurologic function. From an overall standpoint as a society, do we want to continue using a treatment that while would increase the chance of survival, may decrease the chance of meaningful survival?

Perhaps we need to find that sweet spot where we are giving just the right amount of epinephrine during cardiac arrest, not too much and not too little. The study group performed several subgroup analyses that are detailed in the study appendix, however one that was not performed was looking at favorable neurologic outcome by number of epinephrine doses. Prior research in the late 1990s demonstrated worse outcomes for escalating and high dose epinephrine. Perhaps the average 4.9 doses of epinephrine given in this study is still too much?

The authors also make a very valid point in looking at the number needed to treat for benefit for various interventions during out of hospital cardiac arrest. The number needed to treat for epinephrine to prevent one death after cardiac arrest is 112, while the number needed to treat for early recognition of cardiac arrest is 11, bystander CPR is 15 and early defibrillation is 5. Perhaps as a society, we need to view out of hospital cardiac arrest as a PUBLIC HEALTH issue and not a public safety issue and focus on strengthening these links in the chain of survival.

As has happened with each revision since the 2000 guidelines, less emphasis is being placed on medications and more on chest compressions, bystander CPR and bystander defibrillation. Is epinephrine dead yet? I don’t think so but it looks pretty bleak for our old standby. And rightfully so. Again, most people polled would want to recover from cardiac arrest in reasonably good neurologic shape and return to activities they enjoy, not to populate long term care facilities.

Resources:

Perkins GD, Deakin CD, Quinn T, Nolan JP, Scomparin C, et al. A randomized trial of epinephrine in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. NEJM Jul 18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1806842. [Epub ahead of print]. (article) (supplementary appendix)

Callaway CW, Donnino MW. Testing epinephrine for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. NEJM Jul 18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1808255. [Epub ahead of print]. (editorial)